Rare icy formations appear along the Baltic Sea coast, drawing scientists’ attention

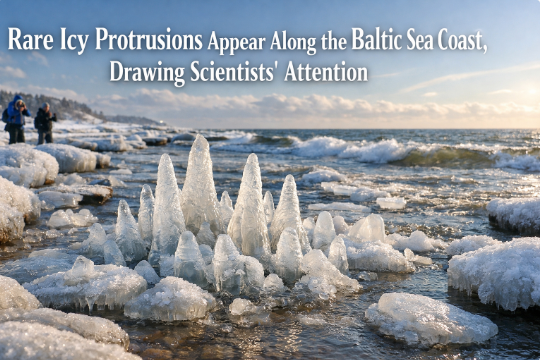

When the Baltic Sea turns theatrical, it doesn’t do it halfway. In mid-winter, as continental winds sweep across Scandinavia and Northern Europe, the usually subdued shoreline can morph into a gallery of fleeting sculptures—rounded “ice balls,” delicate “pancake ice,” ribbed “ice ridges,” and fractal “shorefast” and “anchor ice” that cling to rocks like crystal moss. This week, rare icy formations along stretches of the Baltic Sea coast have captivated locals and visitors alike, and—more importantly—have prompted scientists to make swift field visits. The result is a convergence of curiosity and research: a moment where coastal beauty intersects with the physics of ice formation, oceanography, and climate variability.

A once-in-years spectacle, explained simply

What makes these formations “rare” isn’t that the Baltic never freezes—it does, especially in the Gulf of Bothnia and the Bothnian Bay—but that the timing, location, and diversity of shapes have coincided along more southerly and wave-exposed beaches. For ice balls to roll into existence, you need a cocktail of cold air, near-freezing water, steady surf, and small seed particles that can accrete layers of frazil ice (fine, slushy crystals). For pancake ice—those neat, circular discs with raised edges—you need a similar slush, plus gentle wave action that causes the rims to thicken as plates bump together. Shorefast and anchor ice demand supercooled water and calm micro-environments; they lock onto substrates, then grow outward in branching patterns. When all of these appear within the same coastal stretch, the scene reads like an illustrated encyclopedia of sea-ice dynamics.

Beneath the charm is straightforward thermodynamics. Sea water in the Baltic is brackish, not fully saline like the North Atlantic, which slightly raises its freezing point relative to ocean water. Combine that with sharp radiative cooling overnight, wind chill, and repeated wave agitation, and you create a laboratory in the wild. The Baltic’s narrow, semi-enclosed geometry can reinforce these conditions by limiting major swells yet allowing persistent fetch in certain bays. That’s why some beaches can be bare while the next headland over hosts a field of ice pancakes, each spinning slowly in the surf.

Why scientists rushed to the shore

The Baltic Sea is one of the most intensively observed marginal seas on the planet, with research stations, coastal universities, and citizen-science networks that report unusual events. When these icy formations appear in unusual abundance, researchers mobilize for a few reasons:

Baseline and variability: Long-term datasets depend on capturing unusual events. The extent, thickness, and structure of seasonal sea ice vary year to year with large-scale climate patterns like the Arctic Oscillation and the North Atlantic Oscillation. Recording the timing and spatial pattern of rare formations helps refine models that predict ice cover, coastal flooding, and seasonal navigation conditions.

Coastal processes and erosion: Icy formations interact with waves and sediment transport. Pancake fields and shorefast ice can dampen waves, temporarily shielding dunes; ridges can trap beach sediment; and breaking ice in the surf zone may accelerate abrasion of rock or timber. Documenting these interactions informs coastal management, especially for low-lying communities facing stronger winter storms.

Ecosystem windows: Ice edges are biologically lively. Diatoms and cold-tolerant phytoplankton can bloom in thin ice or beneath frazil slush, creating microhabitats that feed zooplankton and small fish. These short pulses can echo up the food web to seabirds and seals. Researchers seize the moment to sample water chemistry, chlorophyll, and microfauna while the formations persist.

Technology testing: From thermal cameras and drones to machine-learning classifiers that detect ice type in aerial imagery, unusual events are perfect proving grounds. Aerial transects taken during these episodes help validate how well satellite algorithms distinguish pancake ice from brash ice and open water—vital for navigation advisories and environmental monitoring.

What conditions set the stage this week

The shorthand is “cold snap plus consistent wind,” but the script is subtler. Over recent days, a high-pressure system settled over Northern Europe, clearing skies and allowing rapid nighttime cooling. Along the coast, onshore winds of moderate strength kept a steady, laminar break of small waves—enough to knead the frazil slush into discs and spheres, but not so powerful as to break them apart. Air temperatures remained below freezing through the diurnal cycle, so the formations did not melt between tides. Crucially, the water in the surf zone hovered in the supercooled range near the freezing point of brackish water, letting frazil crystals grow as the waves churned.

Local bathymetry amplified the effect. Gentle, sandy beaches with shallow slopes provided wide intertidal zones where slush could accumulate and rotate, while pebbly stretches offered nuclei for ice balls to accrete. In coves and behind groynes, calmer eddies allowed anchor ice to bloom on submerged stones. Meanwhile, headlands experienced colliding wave trains, which pressed pancake edges together into thicker rims—the raised “collars” that make them so photogenic.

Voices from the shore: what residents are seeing

Residents describe the soundscape as much as the sight: a soft clinking, like glass marbles in a velvet bag, when rounded ice bobs in the wash. As the tide shifts, colliding pancakes clatter gently; every so often a larger swell flips a disc, exposing a clean, white underside. Children toss stones and watch them skid across a field of circular plates; photographers crouch low to capture the ridged halos and honeycomb texture. Walkers note the odd patchwork—bare sand in one pocket, an ice “cobblestone” carpet in the next—mirroring how small differences in current and shelter decide which formation dominates.

Science brief: how each formation grows

Frazil ice: The seed. Turbulent, supercooled water forms tiny crystals that look like snow in a snow globe. These crystals are sticky; they latch onto anything, including each other.

Pancake ice: As frazil accumulates at the surface, wave action organizes it into circular plates. Edge collisions create thickened rims—picture a cookie with a raised crust—while plate-on-plate rafting thickens the field.

Ice balls (or “ice eggs”): Less common. A small nucleus—often a pebble, shell, or hardened slush—rolls back and forth in the surf, acquiring concentric layers as spray and frazil freeze to it. With enough time and consistent tumbling, you get remarkably spherical shapes that can range from ping-pong balls to footballs.

Anchor ice and shorefast ice: In calmer, supercooled water, crystals adhere to rocks, ropes, and vegetation, growing outward in feathery branches. At low tide these can emerge as intricate, crystalline skirts.

Ridges and hummocks: Where ice plates pile against each other, wind and waves shove them into low ridges. On larger scales this resembles Arctic pressure ridges; on Baltic beaches it’s a miniature model that still reshapes swash patterns.

Why this matters beyond the photo

It’s tempting to file these scenes under “winter curiosities,” but they’re more than that. The Baltic Sea is a sentinel system for climate signals because it’s shallow, semi-enclosed, and sensitive to temperature and salinity changes driven by river runoff and North Atlantic inflow. The number of “ice days,” the thickness of shorefast ice, and the timing of freeze-up and break-up tell a story about regional climate variability. Long-term observations show that ice conditions have been trending downward in some parts of the Baltic over recent decades, even as year-to-year swings remain large. That makes rare, extensive formation episodes both scientifically valuable and culturally resonant.

These events also highlight how coastal communities adapt. Harbors schedule icebreaking, ferries adjust routes, and fishers navigate between protective ice dampers and hazardous slabs. On tourist beaches, local authorities weigh public safety—icy rocks and unstable slabs are real slip hazards—against the draw of visitors. Every winter brings a new negotiation between human plans and the sea’s variable mood, and this week’s show is a vivid reminder.

How researchers study the formations—fast

Because such events can vanish with a change of wind or a warm front, scientists rely on rapid-response protocols. Typical steps include:

Drone mapping: Pilots fly grid patterns to create orthomosaics—stitching dozens or hundreds of images into a single, scaled map. From there, researchers quantify disc sizes, field density, and rim thickness using computer vision.

In situ measurements: Teams collect water temperature and salinity profiles in the surf zone, verify supercooling, and sample frazil crystals for size distribution. Simple tools—fine nets, insulated buckets, calibrated thermometers—combine with high-resolution loggers.

Acoustic and thermal imaging: Underwater microphones (hydrophones) and thermal cameras can detect freezing processes and plume structures invisible to the eye, revealing where anchor ice is most active.

Community science: Apps and hotlines let residents submit geotagged photos, which, when corrected for lens distortion, become usable for mapping. Crowd observations extend reach well beyond formal research stations.

Practical guidance for visitors and photographers

If you’re planning a shoreline visit to see these formations, a little preparation goes a long way.

Check tide and wind: Pancake fields expand and contract with wind direction and strength; a modest onshore breeze at low tide typically offers the best view of rims and collisions.

Dress and tread safely: Ice-glazed rocks are treacherous. Use crampon-style grips, avoid stepping onto floating plates, and keep a respectful distance from breaking slabs.

Photograph smartly: A polarizing filter helps cut glare and reveal texture. Low angles at sunrise or late afternoon will make rim shadows pop. For scale, include a glove or coin near—but not on—fragile features.

Respect habitats: Avoid trampling dune grasses and intertidal life. The formations are transient; the ecosystems they overlay are enduring.

Looking ahead: what these formations might tell us

If conditions persist, scientists expect a brief evolution. Pancake ice can either consolidate into a quasi-continuous sheet—smoothing surf—or fragment if wind shifts. Ice balls may grow slightly larger but will likely strand as the surf line retreats with changing pressure. Anchor ice can detach en masse, rising like ghostly bouquets. Each pathway encodes information about heat exchange, salinity gradients, and the interplay between waves and ice. When merged into seasonal datasets, these snapshots improve forecasts that matter to shipping, fisheries, and coastal planning.

There’s also a broader narrative. Spectacles like this bind communities to place. They inspire school field trips, fuel local news stories, and nudge adults to relearn the names for winter’s many textures: frazil, pancake, brash, nilas. Knowing these terms isn’t trivia—it’s a vocabulary for paying attention. When attention sharpens, stewardship usually follows. People who notice winter’s subtleties are often the same people who volunteer for beach cleanups in spring and heat-wave relief check-ins in summer. Climate literacy grows through repeated, concrete encounters with the living coast, and the Baltic’s winter grammar is one of its most engaging teachers.

Frequently asked questions (for readers arriving via search)

Are icy balls and pancake ice harmful to marine life?

In general, no. They’re natural phenomena. However, abrupt formation and break-up can disturb intertidal organisms, and shorefast ice can temporarily alter access for foraging birds. Most effects are short-lived.

Do these formations mean the winter is more severe than average?

Not necessarily. They indicate a local alignment of conditions—air temperature, wind, and near-shore currents. Some winters with modest regional cold can still produce spectacular local events.

How long will the formations last?

From hours to several days. A warm front, strong swell, or wind shift can dismantle them quickly. Calm, cold nights favor persistence and growth.

Where are they most likely to appear again?

Shallow, gently sloping beaches with consistent, moderate surf are good bets. Sheltered coves are best for anchor ice; open sandy stretches favor pancakes and ice balls.

Can I collect an ice ball as a souvenir?

They melt fast. Better to take photos—and remember that removing natural features from protected areas may be discouraged or restricted.

Final thoughts

The Baltic Sea’s winter isn’t only about frozen harbors and quiet piers. It’s also about sudden artistry—physics made visible—filling the intertidal with shapes that look designed despite being completely emergent. Scientists love moments like this because they’re data-rich, testable, and finite. Locals love them because they’re beautiful and rare. Together, those loves produce something priceless: attention tuned to a living coastline. Keep your eyes open, your boots steady, and your curiosity warm.

SEO Keywords Paragraph:

Baltic Sea rare icy formations, Baltic Sea ice balls, pancake ice on Baltic beaches, anchor ice and shorefast ice, winter coastal phenomena, sea ice dynamics, Baltic climate variability, coastal erosion and ice, oceanography research Baltic Sea, drone mapping of ice formations, frazil ice in surf zone, cold snap Northern Europe, Arctic Oscillation influence Baltic, sustainable coastal tourism winter, photography tips icy beaches, Baltic Sea weather patterns, brackish water freezing point, shoreline safety in winter, marine ecosystem under sea ice, citizen science coastal monitoring, ice ridges on Baltic coast, Bothnian Bay winter ice, environmental change Baltic region, seasonal sea-ice forecasting, visiting Baltic beaches in winter.